Lab-Grown Diamond Prices Are Falling. Here’s Why That’s Not a Bad Thing.

Scientists discovered the ability to create synthetic diamonds back in 1954, and we’ve been arguing about them ever since. Not only about whether a man-made gemstone could be considered the same as one produced by geologic phenomenon over the course of eons—the two are chemically identical, after all, and indistinguishable to the naked eye—but also about whether it should be. Lab-grown stones have always seemed to solve for certain ethical and environmental conundrums within the diamond industry, but as human beings, we also like our rarities, well, rare. It’s a debate, in other words, over whether diamonds are still “forever” if they’re also for everyone.

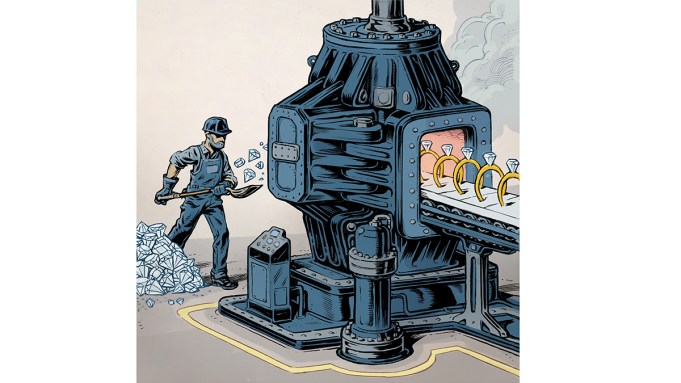

But the market has seemingly made up its mind, at least when it comes to adornment. Allied Market Research valued the synthetic-diamond industry at $24 billion as recently as 2022, but in May, De Beers—a longtime proponent of man-made—announced that its lab-grown offshoot brand Lightbox would permanently reduce its prices from $800 to $500 per carat. Sandrine Conseiller, CEO of De Beers Brands, credits the adjustment to the “high volumes of supply coming online in China and India” and says the decision “reflects the broader trends that we’re seeing across the lab-grown-diamond sector.” Later that month, at the JCK Show trade event in Las Vegas, a separate announcement touted De Beers Group’s new five-year “Origins” strategy, intended to “grow value and revitalise desire for natural diamonds.” As part of that plan, the group’s Element Six subsidiary, which specializes in synthetic-diamond development, will cease all production meant for jewelry in order to focus entirely on industrial applications.

So is it game over for the synthetic-diamond industry? Helen Molesworth, senior jewelry curator at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum and author of Precious: The History and Mystery of Gems Across Time, admires how the technology “makes one of the most revered materials of all time accessible to all” but also notes that “synthetics don’t fulfill the traditional definition of precious gems, which must hit three different criteria: beauty, durability, and rarity. Lab-grown diamonds are obviously beautiful and durable, exactly like their natural counterparts, but they’re not rare. The fact that they are created by us and not by the Earth removes some of that magic, that sparkle.” To say nothing of the fact that synthetic stones require staggering amounts of energy to create, and, according to Conseiller, “the vast majority of lab-grown diamonds are produced in China and India using fossil fuel–based electricity,” meaning one of the purported environmental benefits of choosing synthetic largely goes out the window.

And yet a diamond, no matter how it’s produced, boasts remarkable material benefits. It’s the hardest naturally occurring substance on Earth—even high-tech creations such as aggregated diamond nanorods, a.k.a. hyperdiamonds, can’t much improve on it—and undeniably alluring to the human eye. Plus, fabricated stones can be physically manipulated in ways the “real” deal can’t. Just take the eye-popping TAG Heuer Carrera Plasma chronograph, which has irregularly shaped diamonds not only incorporated on the dial and as hour markers but also seamlessly integrated within the case and bracelet, while the crown itself is a single diamond, lab-grown to the perfect shape. Most if not all of that design would be impossible using the naturally occurring version. Perhaps what the lab-grown industry needs, then, is less hectoring and more ingenuity.

“Created diamonds give you the ability to go outside of your traditional lines, to visualize and imagine product that couldn’t be created with Earth-mined [stones],” says Amish Shah, of New York–based lab-grown specialist ALTR. As an example, Shah describes a customer who requested ALTR’s help with the roof design for a customized car that included interior laser lights: They wanted gray and black diamonds grown to match the color of the headliner “so that when the lights are turned on, there would be refraction” throughout the cabin. “It’s the only car of its kind that has been produced with these lights and diamonds mounted in the roof,” he says.

Or take Hong Kong–based the Future Rocks, which produces diamond rings that are, quite literally, rings of diamond: Even the band is made from created stone. “The Ring band is from one single piece of lab-grown white sapphire—it was originally 60 carats, and we handcrafted it down to six to eight carats,” says Anthony Tsang, the company’s cofounder and CEO. “Then, on top of that, we designed the 18-karat-gold basket into which we put the two-carat lab-grown diamond.” The brand recently debuted a version called Blondie in striking canary-yellow diamond. “These are the sort of things we believe lab-grown diamonds and lab-grown gemstones should gravitate toward,” he says, calling the approach “designing innovation.”

“What’s naturally going to happen is that there’s going to be a separation of the two industries, financially and emotionally,” Molesworth, the author, predicts, and that already seems to be underway. So why not lean into it? Why not incorporate created diamonds (or other gemstones) into furniture, automobiles, home goods, and yachts? We live in an age when artificial intelligence promises (or threatens) to conjure the highest levels of human creativity—the likes of Don Giovanni, Hamlet, the Sistine Chapel—on a whim, in mere minutes. But A.I. and lab-grown diamonds are themselves products of human ingenuity, which means their use is also our purview.

“We wear gems to say something about ourselves—who we are as individuals, what tribe we belong to and our place in society, what we believe in, and what matters to us most,” Molesworth says. That will no doubt continue to be true, but in a world where scarcity is a problem already solved by technology, what we might put on display with diamonds, instead, is something even more precious: our imaginations.

Nick Scott is the editor in chief of Robb Report U.K. In the London-Essex overlap where he spent his formative years, the word “diamond” most often preceded the word “geezer.”